With the start of the 2021 MLS season just around the corner, fans are checking back in to catch up on what’s happened to their favorite team and their opponents during the offseason. Who added a talented young player from South America? Who brought in a savvy veteran to provide leadership? Who cut bait on a disappointing prospect? Who’s taking a flyer on a low-risk gamble in the hopes it pays off? While most player acquisition takes into account fit and need as primary considerations, in a salary cap league like MLS, it’s impossible to ignore the role that budget plays in assembling a team. And in MLS, that means getting at least comfortable with the concepts of Designated Players, allocation money and a host of quirky carve outs and lacunae created for specific cases. We’re here today to try to help make at least a modicum of sense of how it comes together.

It helps to have an appreciation of just what all these mechanisms are trying to achieve when it comes to building a roster, and it’s not as obvious as you might think at first. When MLS played its first season in 1996, soccer was hot in America on the heels of the United States hosting the World Cup in 1994, but it wasn’t quite hot enough for millions of dollars to be thrown out willy-nilly. From the start, MLS has been a salary cap league, meaning there are limits on how much a team can spend on its roster, much like the NBA and NFL. The goal was sustainability, and having seen leagues like the NASL fold after some teams spent big on international players while others barely paid their players anything, MLS was intent on keeping history from repeating itself. Rather than independent entities, the teams were franchises of MLS itself, and the league controlled and paid the players’ salaries. While this was not without controversy, it did manage to keep the league afloat through its early, lean years as it worked to establish itself. To this day, the checks that pay the players are cut by the league, not by the individual teams.

Before we dive into how the salary cap functions, let’s establish some terms. A player’s salary is what they are paid. This is what you see under base salary when the MLS Players Association releases player salaries. A player’s budget charge is their salary plus things like transfer fees and other associated fees. This distinction is useful because the budget charge really represents their monetary impact on the budget. Their salary will always be their salary, but as we go forward, we’ll see how different mechanisms can be used to change how their budget charge fits into the cap.

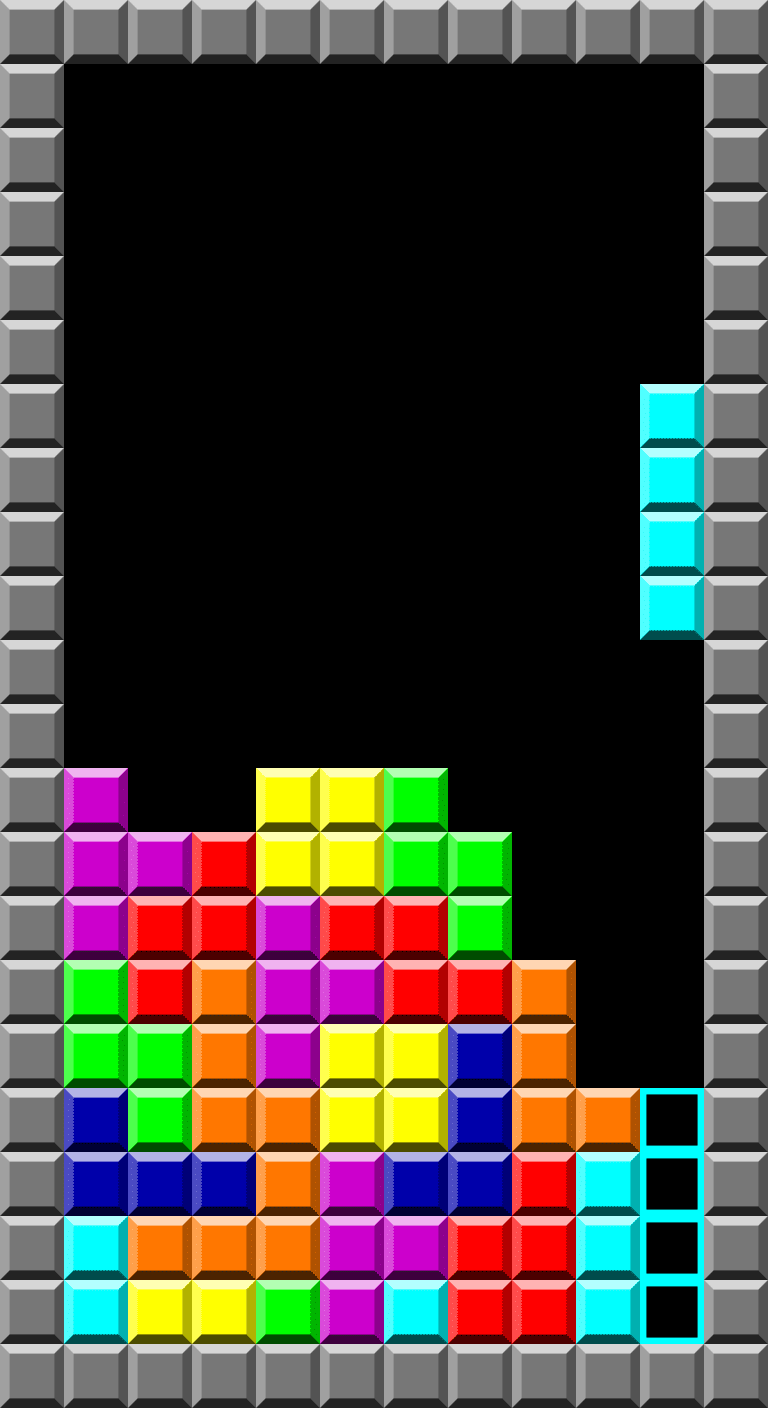

For the time being, let’s put aside those mechanisms and imagine a very basic, imaginary roster under the salary cap. The salary cap for 2020 was $4.9 million and roster spots 1-20 count against this cap, with the minimum budget charge being $81,375 and the maximum budget charge being $612,500. (In actuality, teams can have up to 30 players and there are plenty of rules about those 10 “supplemental” roster spots that are often filled by homegrown players, players on Generation adidas contracts or other reserve players but all you need to know for right now is that they don’t count against the cap.) The numbers were smaller — much smaller — but this is fundamentally how MLS worked in its first decade. Teams would mix and match budget charges to get everyone fitting under the cap, sort of like playing Tetris with all square blocks that fit nicely together.

Structuring the league in this way enhanced both sustainability and competition, at least initially. Teams had to do the best they could within financial limitations, ultimately keeping one team from running away with the league year in and year out. It also kept budgets low enough that teams generally could stay in business despite sizable losses in the early years. MLS was not then and is not now a top tier soccer league globally. It occupies a particular place in the worldwide soccer landscape and if teams were paying “just okay” players way more than they were worth, it would have made growth impossible. This structure fostered that growth, but as the league grew and opportunities expanded, this initial setup revealed its limitations.

Enter David Beckham. In 2007, the Designated Player rule was created to allow the LA Galaxy to bring in Beckham, a move that would raise the profile of the league considerably both domestically and abroad and ultimately pave the way for many stars to come. The basic concept behind the rule was that while MLS would pay any player up to the maximum budget charge, they would now allow a certain number of players to be paid more than that, with the club footing the bill for everything over the max. Thus, clubs could pay a premium to get players who commanded more money but who would also significantly raise the top end of a team’s talent level. To return to the Tetris metaphor, teams still had to fit their blocks under the cap — or the top of the well — but in a few cases, much longer blocks could stick up above the top of the well with the club paying out of pocket for them.

MLS teams operated in this world for a number of years, with teams now able to bring in stars like Diego Valeri (Portland Timbers), Clint Dempsey and Obafemi Martins (Seattle Sounders), Robbie Keane (LA Galaxy), Thierry Henry (New York Red Bulls) and others. With an eye once again on balancing stability with competitiveness, though, MLS began to work on a way to improve the depth of rosters without simply allowing teams to spend more and more of their own money on more DPs. This led to the introduction of allocation money in 2015.

There are two kinds of allocation money: general allocation money and targeted allocation money. Generally speaking, GAM is the common currency of MLS, with teams receiving a fixed allotment each year and using it to make trades for players while working to keep a good quantity of it at the ready in order to effect those moves. It’s important to note that the quantity of GAM in MLS is more or less fixed. It moves around from team to team but isn’t acquired or sold outside of the league, except in cases when players are sold at a profit. In that situation, a portion of the profits can be taken as GAM. Different teams have different ideas about how much GAM they want to have on hand, but generally, teams with a good amount of GAM can be buyers in transfer windows while teams who find themselves strapped for GAM have to become sellers. GAM can be used to straight up move players or it can be added into trades to balance them, and it can be distributed over a number of years.

Targeted allocation money — or TAM — has evolved a great deal over the years. In MLS today, it’s spent at the discretion of teams, up to a max of $2.8 million, and it’s a little more restricted than GAM in its uses. While both GAM and TAM can be used to buy down budget charges (more on this specifically in a moment), TAM can only be used on players making more than the maximum budget charge. For that reason, TAM is mostly used to allow the team to add quality players beyond a team’s DPs.

Take a breath. It’s a lot. The big picture here is that the salary cap remains a means to create a level playing field across a league where parity is high. Every team has $4.9 million of space for players to occupy on the budget. Designated Players are exceptions that can exceed the maximum budget charge and allocation money is a mechanism for adjusting budget charges so they can still fit under that cap. Let’s dig into that a bit more.

Teams need to take all of their budget charges for players — minus the DPs as exceptions — and make them fit. Every player whose budget charge is less than the individual max? No problem, just fit them under the cap (or use GAM to buy down larger salaries to make fitting even larger salaries possible). Players whose budget charge is more than the max? There’s some calculating to be done to figure out how they’re labeled for budget purposes. As we mentioned earlier, a player’s budget charge incorporates all the costs of a player (salary plus transfer fee plus agent fees plus miscellaneous costs) into one number. Average that out over the life of their guaranteed contract and you get their average yearly budget charge. Right now, if that average yearly budget charge is more than $1.6 million, the player has to be a Designated Player — simple as that. If it falls in that million between the $612,500 max budget charge and the $1.6 million point where DP status starts, that’s where targeted allocation money can be used.

The Tetris illustration is instructive here. You have all the budget charges on the roster piled up neatly to the cap, plus the Designated Player salaries that stick out above it. As you add on these budget charges that go over the cap, they stick out like the DP charges, only not quite as high. You can then drop allocation money around those budget charges and boom: lines clear and you re-establish everything (except for DPs) below the cap. In many cases, teams will even adjust budget charges below that $612,500 down to a minimum of $150,000 in order to spend more on other salaries. Thus, a player whose budget charge is more than $1 million may end up only counting for $150,000 against the cap in adjusted budget charge.

When everything is balanced — when the Tetris blocks have been dropped and everything fits — it’s a temporary victory, because a team’s roster budget is an ever-shifting jigsaw puzzle. Each decision about a player is made with one eye on how things have been set up before and one eye on what the team believes will happen in the future. As that framework moves through time, things inevitably change. Players improve, fall off, get injured, get restless, get offers. Teams change coaches or front offices or even owners. Or, you know, a global pandemic happens. And all this is happening daily not just for your team but for the 26 other teams in MLS, not to mention all the teams in all the other leagues that players are arriving from or departing for. And keep in mind: many of those other leagues don’t have salary caps, which makes coming to terms sometimes difficult and laborious. This is one of the reasons deals to bring players in from other leagues can take a long time.

Feeling a little lost? That’s okay. There’s a reason clubs often have a person whose entire job is dealing with this and more or less only this, and it’s because you need to cultivate both an intense investment in the micro elements of this stuff and also a capacity to see the big picture of it. There’s a term that originated in science fiction that then migrated to computer science — the verb “to grok.” It means to perceive intuitively or sort of grasp inherently through a combination of knowledge and experience. These cap experts grok the salary cap. Hopefully, you’ve gotten just a bit of a feel for it.